Back to the Future: The Return of US Manufacturing

- jpetricc

- Apr 21, 2025

- 17 min read

Implications for National Security and the Financial Markets

The United States has placed a baseline tariff of 10% (with reciprocal tariffs on pause) across the board on all countries, and multinational companies are moving rapidly to adjust their global supply chains. These adjustments will in turn reconfigure global trade flows at an unprecedented speed. In this note we look at what the White House is trying to accomplish with the tariffs and the implications for the US financial markets both in the short-term and long-term.

Before we get to the effect on the markets, let’s establish the state of the US economy as of Q4, 2024 and the purpose of the trade policies.

US Economy

Corporate earnings results for the fourth quarter are fully out and on average firms grew earnings by 18.2% (the most in four years), while revenue grew by 5.3%. This was the 17th consecutive quarter of revenue growth. Businesses appear to be in good shape both in terms of revenue growth and cost control. The economy in general was also solid in Q4, 2024 as GDP and consumer spending grew by 2.4% and 4.2% annualized, respectively.

Trade Policy Purpose

The purpose of the trade policies adopted by the White House in enacting tariffs include several ancillary goals ranging from eliminating non-tariff trade barriers in other countries (namely regulatory barriers), to reducing foreign trade subsidies, to reducing the trade deficit, to increasing tariff revenues to reduce the United States’ federal budget deficit. The achievement of these fair-trade goals will be very helpful to the US economy, but to forecast future impacts it is more important to understand the primary and long-run goal of these policies: To increase national security.

Executive Order 14257 (EO), which enacted both the baseline and reciprocal tariffs, states that, “[…] the absence of sufficient domestic manufacturing in certain critical and advanced industrial sectors […] compromises US economic and national security.” The EO continues by highlighting how, “Both my [Trump] first administration in 2017 and the Biden administration in 2022 recognized that increasing domestic manufacturing is critical to US national security.” Driving this point home, the EO states that,

“[…] if the United States wishes to maintain an effective security umbrella to defend its citizens and homeland […] it needs to have a large upstream manufacturing and goods-producing ecosystem to manufacture these products without undue reliance on imports for key inputs.”

Acting in a PR capacity, Howard Lutnick, the Secretary of Commerce, gave an interview for Bloomberg in mid-March and clearly advocated for the tariffs and stressed the underlying reasoning for them when he proclaimed, “Listen to the President! National security matters! When he calls out [sectors] like semiconductors, he calls out pharmaceuticals, he calls out autos, these are things that matter to us as a country […] the President has said there are certain products I need to have us make in America.”

These quotes imply that there is a national security problem that the White House is urgently trying to fix with the imposition of tariffs, which leads to the big question: What precisely is this national security problem?

Achieving national security requires many things, but where the White House sees a hole is in the ability of the US to fight a protracted war against a super-power country.¹ To understand this more deeply it is useful to go back to the last time the US was in this situation, which was World War 2. The key to the US and its allies winning that war was the strength of US manufacturing and, specifically, the ability of the US to manufacture military and supporting equipment.

In 1941, the US produced more ships than Japan did during the entire war. In 1944, the US produced more planes than Japan did during the entire war. By the end of the war, US companies had produced more than two-thirds of the total military equipment that the Allies used during the war. US industrial output doubled in a matter of four years, and this overwhelmed Germany, Japan, and the other Axis countries. As a result, by the end of the war US industrial output was greater than the rest of the world’s combined. In this context, the current White House views the ability to match or out-produce opposing countries as a crucial element to winning a major, protracted war. This is given strong emphasis in the EO as it states,

“[…] a nation that does not produce manufactured products cannot maintain the industrial base it needs for national security […]”

To understand this more let’s look at a current real-life example. In the Russian-Ukraine war, while most analysts predicted a quick victory by Russia, Russia’s inconsequential manufacturing sector (less than 2% of global manufacturing output and less than 1% of industrial output) was a key indicator that it would have a difficult time in a protracted war, as it has. It’s been three years since that war began and Russia now occupies about 18% of Ukraine (not including Crimea which was occupied previously).

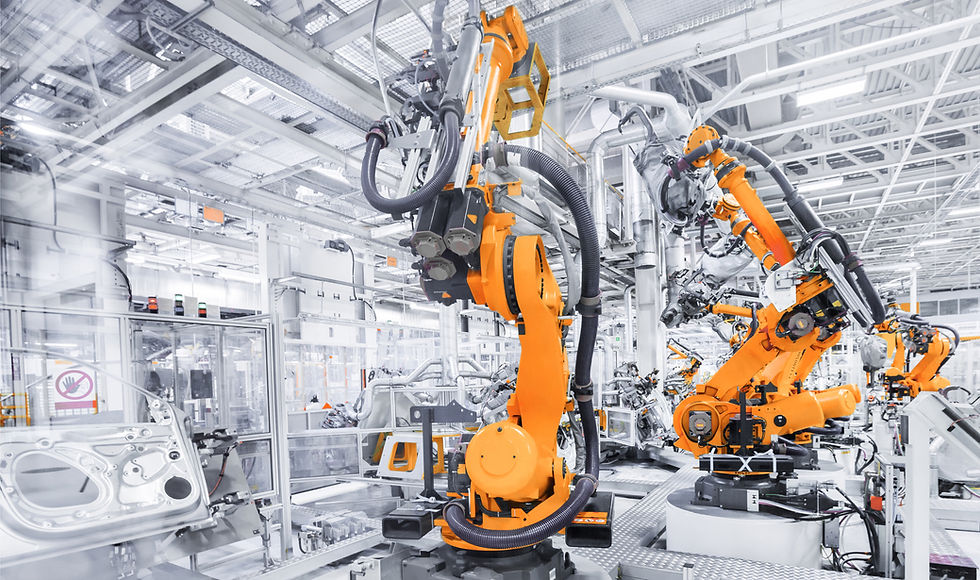

Today, the US is second in the world in manufacturing output with about 15.9% of global manufacturing.² While still substantial, the manufacturing ability of the US is greatly diminished since its peak at the end of World War 2. Importantly, the key for the US during World War 2 was its ability to take existing commercial manufacturing and convert it to military purposes. The auto industry is a perfect example of this.

In 1941, the US auto industry built about 3 million vehicles. During the war, the US auto companies all converted to defense manufacturing, and only 139 consumer vehicles were produced during the rest of the war. General Motors, which had been the largest auto manufacturer in the world, became the largest defense contractor in the world, producing airplane engines, guns, military trucks, and tanks.

With its existing manufacturing sector, the US is potentially capable of ramping up its manufacturing substantially for war purposes. But, as global manufacturing has evolved, several chokepoints have emerged in US defense manufacturing. The easiest way to understand these chokepoints is through a few examples.

Critical and Rare-Earth Minerals

Critical and rare-earth minerals have become essential in the manufacturing of a host of weapons. Tungsten, for example, is a key ingredient in a large variety of applications, from household items to sophisticated medical equipment. Tungsten has the highest melting point of all metal elements, with a density close to gold and hardness (in tungsten carbide) close to diamond. Because of this unique combination of properties tungsten has no substitute for its use in artillery shells and parts, armor-piercing bullets and shells, missiles, armored tanks, and engines for fighters and rockets. It also has wide industrial use, from cutting tools and drilling equipment to semiconductor chips and aerospace equipment.

The chokepoint here is that over 80% of the world’s mining and production of tungsten occurs in China, and another 10% occurs in Russia.³ On February 4, 2025, China announced restricted exports of several critical minerals, including tungsten. This has resulted in substantial delays and price increases in over 3,000 weapons parts requiring tungsten that the US uses. The greatest impact has occurred in the manufacture and maintenance of fighters, with the typical fighter utilizing over 200 parts containing tungsten.

In any prolonged war with China, the ability of the US armed forces to replace everything from missiles and artillery to tanks and fighters would be critically hampered because China (and very likely Russia) would completely cut off the availability of tungsten.

87% of the worldwide production of antimony, another mineral widely used in munitions, is also controlled by China and Russia.

This same story repeats itself for most of the 50 minerals that the US Geological Survey identified in 2022 as critical to national security and the economy.⁴ Of the 17 rare-earth elements that have wide defense and industrial uses, China controls about 90% of their mining and 70% of their processing. The Director of the Critical Minerals Security Program (Gracelin Baskaran) at CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies) stated in an interview with Bloomberg,

“We have seen minerals and even rare earths be weaponized over time.⁵ So for us it’s a national security challenge because rare earths go into almost every form of defense technology, from fighter jets and warships to missiles and tanks.”

This is why the White House has been scouring the globe, from Ukraine to Greenland, trying to find and obtain mineral rights, as well as pushing to develop mineral mining and processing capabilities in the US.

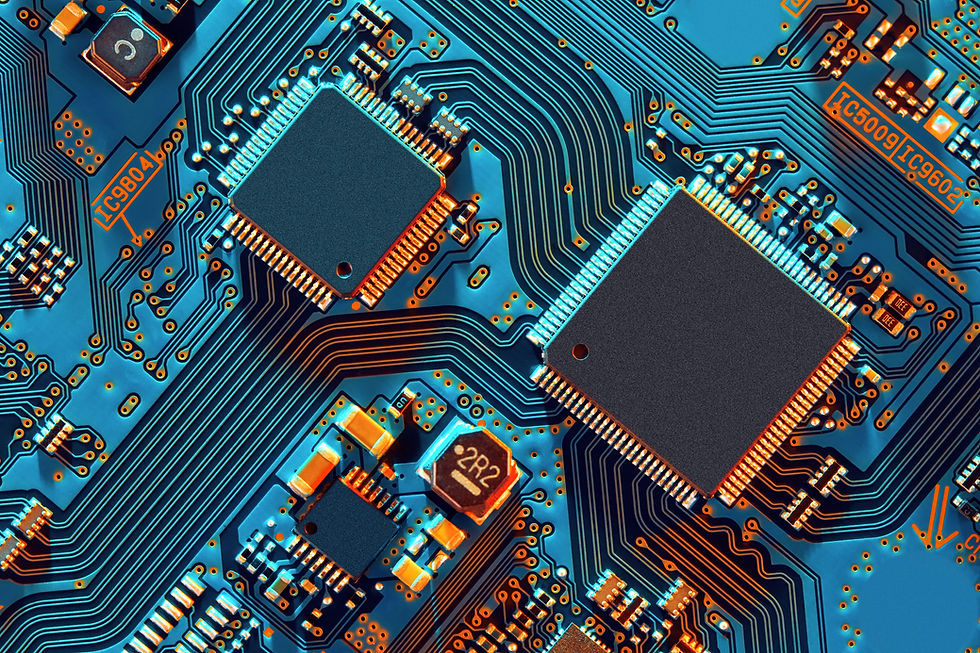

Semiconductor Chips

Going one rung higher on the chokepoint ladder, another issue facing the US defense supply chain is in the manufacturing of semiconductor chips. Semiconductor chips are used in everything from smartphones and refrigerators to missiles and fighter jets. The US consumer recently got a feel for the supply chain bottleneck here while coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time, the lack of chip availability for doing simple tasks like turning on windshield wipers and raising and lowering car windows led to significant shortages of new cars on dealer lots and substantially raised the prices of new and used cars. This story repeated itself in product after product requiring semiconductor chips in the consumer, industrial, and military segments, and was one of the primary reasons for the surge of inflation in 2021.

While the design of semiconductor chips is widely distributed across many firms, the manufacturing of chips is concentrated in one firm: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). TSMC manufactures about two-thirds of all chips used worldwide and 90% of the leading-edge chips.⁶ TSMC’s clients are a long list of the biggest tech and semiconductor design firms in the world and include Apple (in their semiconductor design operations), Nvidia, AMD, Intel, Qualcomm, Broadcom, and MediaTek. Chips designed by these firms in turn feed into virtually all consumer, industrial, and military products used in the US.

The chokepoint here is that over 90% of TSMC’s manufacturing is done in Taiwan. Under the “One China” policy, China views Taiwan as a breakaway province that will eventually be reunified with mainland China. If this were to occur, and if the US and China were ever to enter a conflict, 90% of the production of leading-edge chips would be cut off from the US. With the availability of chips effectively cut off, the US industrial and military complex would not last long in a drawn-out conflict with China.

Ships

Going another rung higher on the chokepoint ladder, the availability of ships and shipbuilding represents a significant problem for the US military. In 1950, the US commercial marine fleet represented about 47.1% of the world’s cargo shipping capacity. By 1960, this number was at 16.9%, and today it stands at 0.4%. Currently, China has over 5,500 oceangoing merchant vessels, while the US has 80.

The staggering decline in the number of US ships has also resulted in a significant decline in the number of US merchant marines, a set of commercial sailors who in wartime can quickly transition to assist the US Navy with logistics, supply, and distribution for the Navy’s far-flung operations. During World War 2, the merchant marines were essential in supplying the Allies with weapons and munitions from US factories as well as supplying the US Navy in its widespread naval battles in the Pacific. The US now has about 9,000 merchant marines compared to 103,000 in 1950.

The risk that the US and its military find itself in is summarized by the current National Security Advisor, Mike Waltz, in an interview with Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS):

“From a national security perspective, we talk a lot about China’s ability to turn off things that they now produce and we no longer do — like pharmaceuticals, or rare earth minerals, or the fact that most of our chips are produced now in Taiwan under threat by China. But they literally could turn off our entire economy by essentially choking off that shipping fleet and, conversely, turn theirs into warships or into levers of geopolitical influence. It’s just completely unacceptable.”

On the topic of US commercial shipping ability in an interview with the Wall Street Journal Senator Mark Kelly stated, “It’s a major problem for us, especially if we wound up in a conflict or we wind up in a situation where China decides for whatever reason that they want to stop our economy and put [the] brakes on it in a big way. They have the ability to do that.”

The ability to quickly and exponentially ramp up manufacturing is critical to not losing in a sustained war. Given how US supply chains extend globally, without US ships to transport products across the oceans (about 80% of goods to the US come in on ships), US manufacturing would be severely limited in its ability to ramp up production in any sustained conflict.

The problem does not stop at ships, though, it extends to shipbuilding as well. American shipyards produced 65,000 tons of new ships in 2023. By contrast China’s output in 2023 was 33 million tons of new ships. US shipyards built 5% of the world’s tonnage of ships in the 1970s. Today US shipyards output about 0.1% of the world’s tonnage, while China’s shipbuilding industry outputs over half of the world’s tonnage. In 2023, China received over 1,500 orders for new ships, while the US received 5.

In a protracted conflict with the US, China’s shipyards would be able to ramp up ship production to an even greater amount from its current prolific rate. It could replace lost ships and repair damaged ones at a pace the US cannot come close to matching currently.

Mike Waltz, the current National Security Advisor, said in an interview with CSIS: “The Chinese Navy is growing and rapidly expanding, not just because they are investing in their navy. They’re doing it on the backs of this massive investment and growth in their commercial shipbuilding fleets. So, a shipyard that can produce one of the world’s largest container ships can then pretty easily flip and produce an aircraft carrier, and do it at scale with the workforce, the steel, the aluminum, and the know-how that has been invested and paid for by their commercial shipbuilding industry.”

There are dozens of other examples of chokepoints in areas ranging from biotech to advanced textiles. The importance of manufacturing to the security of the US was stated simply by US Commerce Secretary, Howard Lutnick:

“Let’s make sure the key ingredients that are necessary to defend America are made here in America.”

Finally, the EO summarizes all points national security: “[…] the large, persistent annual US goods trade deficits and the concomitant loss of industrial capacity have compromised military readiness […] Such impact on military readiness and our national security posture is especially acute with the recent rise in armed conflicts abroad.”

So, we can clearly see that for the White House the primary goal of the tariffs is not economic fair trade. While that is a concern, it is not the main concern. The main concern is national security, and specifically the removal of all chokepoints to ensure the uninterruptible functioning of the US economy and military, and ideally its outperformance in a prolonged war with a super-power.

Implications for Financial Markets

The reason the White House is using tariffs to achieve its domestic manufacturing goals (rather than, say, tax policy or subsidies) is simply because tariffs are the most effective tool at their disposal that does not require a Congressional vote. The use of tariffs, however, comes with costs.

Most trade experts expect the baseline tariffs as well as sector-specific tariffs like those on pharmaceuticals and steel & aluminum to be in place permanently. This means that prices of all products will go up permanently. These price increases will be shared between businesses and consumers. So, the US will likely see a combination of consumer price hikes and a deterioration of corporate margins.

One path that the US economy may take is a one-time upward shift in prices economy-wide and a one-time decrease in corporate earnings. The financial markets are always forward-looking and at the time of this writing stock prices (represented by the S&P 500) in the US have decreased by 12.7% over the last 3 months to reflect the expected corporate earnings drop; the upward shift in prices will hit soon as tariff induced price hikes make their way through supply chains and finally to consumers. Higher prices should lead to lower consumer spending. We should see the impact of lower future consumer spending immediately in the form of lower commodity prices, and both spot and forward commodity prices for everything from oil to agricultural products already reflect these expected decreases. Crude oil spot prices have already fallen over 15% in the last 3 months, for example. In this one-time price shift scenario, credit spreads should widen (as they already have begun to) to reflect firms’ lower profitability and increased bankruptcy risk.

Another, and more likely, path for the US economy requires an understanding of the dynamic effects of the upward shift in prices resulting from tariffs. It is first important to note that US economic growth, while currently positive, has been slowing for the last two to three quarters. The JOLTS survey⁷ has shown that the quits rate⁸ among employees has dropped significantly over the last two years to levels not seen since 2014 when the US economy was still recovering from the Great Financial Crisis. Companies are not laying off workers (yet), but the decrease in the quits rate combined with a flatlining of job openings has made it much more difficult for unemployed workers to find jobs, particularly white-collar jobs. This can be seen in a slowdown in real income growth. While real hourly earnings increased by a weak 1.2% over the last year, the average hours worked decreased by 0.6%, resulting in real weekly earnings increasing by only 0.6%. That is about 1% less than consumption growth, which means consumers have been drawing down on savings to continue spending, which is unsustainable. Furthermore, government spending has been a large driver of the economy over the last few years, and it is decreasing as the new administration takes many steps to reduce it. Spending reductions at the state and local government levels have been even greater. Data from the National Association of State Budget Officers indicates that spending out of state general funds is expected to decrease 6% in 2025. As a result of these factors, many economists think that the US is currently in a mild recession.

Adding the effects of tariffs (decreased consumer spending and corporate earnings) to the downward trend the economy already had means that the economy will likely contract, or at least growth will slow considerably. Lower corporate revenues (due to lower consumer spending) combined with lower corporate margins will likely lead companies to reduce their labor costs by laying off workers. Unemployment will continue the trend that has already begun (currently up to 4.2% from a low of 3.4% in April of 2023) and accelerate. Job openings and the quits rate will continue to decrease. The loss of jobs in turn will result in lower incomes for consumers, who will likely respond by pulling back on spending even more and increasing precautionary savings. This in turn will decrease revenues and margins for businesses even more, leading to even more layoffs. And so on. This is a standard recessionary spiral. The White House has already said that they expect the tariffs to result in some pain and this recessionary spiral is the pain they were referring to.

The standard way out of an economic contraction is to break the pattern with enormous fiscal stimulus. The tax cuts act that is currently working its way through Congress and is urgently awaited by the White House is expected to be that fiscal stimulus (it makes permanent the tax cuts of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and creates additional cuts). If the tax cuts are substantial enough, the US should pull out of the economic contraction and resume growth by the 4th quarter of this year or 1st quarter of 2026. A tailwind that may help this resumption of growth is corporate investment; due to the tariffs, companies should begin to invest on the margin in production in the US which would create new jobs. However, corporate investment will be a long-term process, so the beneficial impact to jobs creation this year will be limited.

Typically, when the US economy contracts, short-term and long-term interest rates drop, i.e., we see a downward shift in the yield curve. In fact, the longer maturities in the yield curve drop more than shorter maturities, and the yield curve thus inverts. We are seeing short-term interest rates dropping already. At the time of this writing, the 2-year yield has dropped from 4.36% to 3.77%. The dollar in turn decreases relative to other currencies, which we are also seeing despite the tariffs (which in theory would otherwise strengthen the dollar due to the reduction in the exchange of dollars for goods denominated in foreign currencies). The dollar has depreciated from 157 to 142 versus the yen. And the euro has appreciated from 1.04 to 1.14 against the dollar. The Wall Street dollar index has decreased from 102.2 to 96.2 over the last 3 months. Longer term interest rates are also beginning to decrease, but the yield curve has not inverted yet. There was an initial blip up in the yield curve, but this was as result of hedge funds unwinding Treasury basis trades. ⁹ 10-year and 30-year Treasury yields moved up from 4.01% and 4.41%, respectively, to 4.48% and 4.85% in less than a week. With most of this unwinding finished, the long end of the yield curve began dropping quickly again. Over the last 3 months 10-year and 30-year Treasury yields have gone from 4.79% and 4.98%, respectively, to 4.29% and 4.74%. This process should continue, and the yield curve will likely invert within the next 3 months.

By the time the new set of tax cuts pass (likely just before the Congressional recess begins at the end of July), baseline and reciprocal tariffs for most countries as well as sector-specific tariffs should be set. This will give the business community the new “rules of the road” and should additionally give the confidence to begin making long-term investment decisions. At this point, hopefully, the Fed will also have begun decreasing the Fed Funds rate and, more importantly, expanding money supply.

In a typical economic contraction, in anticipation of the oncoming fiscal stimulus, the yield curve will dis-invert and become strongly upward sloping — long-term Treasury yields will rise substantially, while short-term interest rates remain relatively fixed. Consumer spending will bottom out as expectations for the coming fiscal stimulus kicks in, and firms as a result will stop layoffs and slowly start hiring again. It is at this point also that the equity markets begin moving up. The dollar will also bottom out at the time the yield curve begins dis-inverting, stay relatively flat for a while, and then begin appreciating.

One issue that might delay this process is the Federal Reserve, which controls the short end of the yield curve (through the Fed Funds rate) as well as money supply. The Fed so far has refused to lower the Fed Funds rate and continues to decrease money supply, both of which are the opposite of what one would want to combat a slowing economy. The reason for this is that the Fed is worried about potential inflation effects from the tariffs. It is possible that the Fed is headed toward making another mistake as it made in 2021 when it missed the pickup in inflation due to thinking inflation at that point was transitory. This time, though, the mistake will negatively affect the Fed’s ability to achieve its other mandate: maintaining employment in the US.

If the tax cuts pass in late July, then this inflection point in financial markets should occur sometime in late October or early November this year. It is at this point when earnings announcements from companies about the 3rd Quarter occur. These earnings announcements should indicate a resumption in growth of aggregate corporate revenues and profits, an indication that consumer spending is heading back up. This is when the equity markets will begin picking up again. A significant move upwards will likely begin only in the tail end of January of 2026, when companies begin reporting 4th quarter, 2025 earnings and markets ensure that the US economy has indeed returned to growth again.

The resumption to growth will not make up for the loss of growth in 2025 — it will effectively become a lost year. The equity markets will return to its long-term growth rate, though from a lower starting point.

It is important to note that several factors could easily derail this sequence of events in the markets and make the coming economic contraction deeper and longer (the paths presented here are hypothetical). Examples include other countries responding to the permanent US tariffs by putting up high tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers of their own, the Fed continuing their tight monetary stance, and Congress not passing a sufficiently large set of tax cuts. These are all significant uncertainties, and any of them could delay the inflection point in financial markets.

...

Footnotes

[1] Their focus is on China, but that is because China and the US are the two super-powers in the world today. If the US were able to fight a protracted war against China, it should be able to do so against any other country.

[2] China has the largest industrial output with about 31.6% of global manufacturing, and Japan is third with about 6.5% of global manufacturing.

[3] The US stopped mining tungsten in 2015 for environmental reasons.

[4] The EU’s 2023 Critical Raw Materials Act lists 34 minerals that are critical for its national security.

[5] Gracelin Baskaran is referring here to an incident between Japan and China in 2010 where China cut off Japan from rare earth mineral exports over a dispute regarding the Senkaku Islands, which are claimed by both China and Japan. In response to US tariffs and export restrictions, China has restricted the export of 7 rare earth elements (samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, yttrium) as well as the critical minerals gallium, germanium, antimony, graphite, and tungsten to the US.

[6] These are defined as 7 nanometer chips and below.

[7] The JOLTS survey (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) is a monthly report published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It includes data on job openings, hires, quits, and layoffs.

[8] The quits rate reflects the percentage of employees who voluntarily left their jobs. It serves as an indicator of workers’ confidence in the labor market. A higher rate suggest that employees feel secure enough to leave their current position.

[9] This trade involves holding a long position in a Treasury bond and selling a bond futures contract. Unwinding this trade therefore would entail selling the long Treasury bond position. A systematic unwinding of this trade would result in Treasury bonds decreasing in price due to the selling pressure and Treasury yields going up.

%20copy.png)

Comments